These days, everybody has a headshot. If you don’t know what you’re doing with your eyes, mouth, or jaw to make sure that yours look their best, Peter Hurley is here to instruct you.

Imagine setting aside a wheel of cheese at your wedding. What would it look like if it were served at your funeral?

If you were lucky, it would look like one of the wheels in Jean-Jacques Zufferey’s basement in Grimentz, Switzerland: shriveled and brown, pockmarked from decades of mite and mouse nibbles, and hard as a rock. You’d need an axe to slice it open and strong booze to wash it down. This is the rare cheese you don’t want to cut into when it’s aged to perfection. A fossilized funeral cheese means you lived a long life.

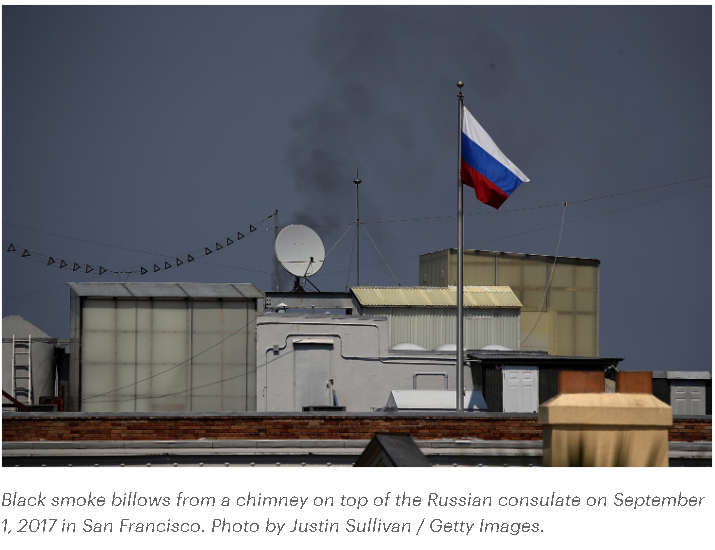

The first thing you need to understand about the building that, until very recently, housed the Russian Consulate in San Francisco — a city where topography is destiny, where wealth and power concentrate, quite literally, at the top — is its sense of elevation. Brick-fronted, sentinel-like, and six stories high, it sits on a hill in Pacific Heights, within one of the city’s toniest zip codes. This is a neighborhood that radiates a type of wealth, power, and prestige that long predates the current wave of nouveau riche tech millionaires, or the wave before that, or the one before that. It is old and solid and comfortable with its privilege; its denizens know they have a right to rule. Indeed, from Pacific Heights, one can simultaneously gaze out on the city, the bay, the Golden Gate Bridge — and, beyond, the vast, frigid Pacific.

Much of the advice you get from so-called success gurus (like “get up before sunrise,” or “work 18-hour days“) virtually guarantees that you’ll fail at the one daily activity that is the foundation of everything: dreaming.

At the start of your career, chances are good that you’ll be hired primarily for your “hard skills”–the stuff you know that’s relevant for the job. When you’re fresh out of college or even a few years into your career, things like what software you’ve mastered, the knowledge you’ve picked up during internships and in school, and your other technical credentials really matter.

One Saturday morning in March 2003, a group of experts gathered at WHO headquarters in Geneva to discuss a newly discovered infection in Asia. Cases had already appeared in Hong Kong, China and Vietnam, with another reported in Frankfurt that morning. WHO was about to announce the threat to the world, but first they needed a name. They wanted something that was easy to remember, but which wouldn’t stigmatize the countries involved. Eventually they settled on ‘Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome,’ or SARS for short.

If cells were personified, each fat cell would be an overbearing grandparent who hoards. They’re constantly trying to make you eat another serving of potatoes, and have cabinets stacked with vitamins they never take.